In 1930, as the United States led the world in industrial output, air travel, and skyscraper construction, more than 90 percent of American farms still lacked electricity. This wasn’t because the technology didn’t exist. Electric lights had illuminated major cities for decades. Refrigerators, washing machines, and radios had become familiar household fixtures for urban Americans. But across rural America, families still cooked on wood stoves, scrubbed laundry by hand, and relied on kerosene lamps after sundown.

The story of rural electrification is not just a tale of technical progress—it is a revealing case study in how infrastructure, ideology, and inequality intersect. It raises fundamental questions that remain with us today: Who deserves access to modern technology? Who pays for it? And what role should the government play in making it happen?

The Unequal Rise of Electricity

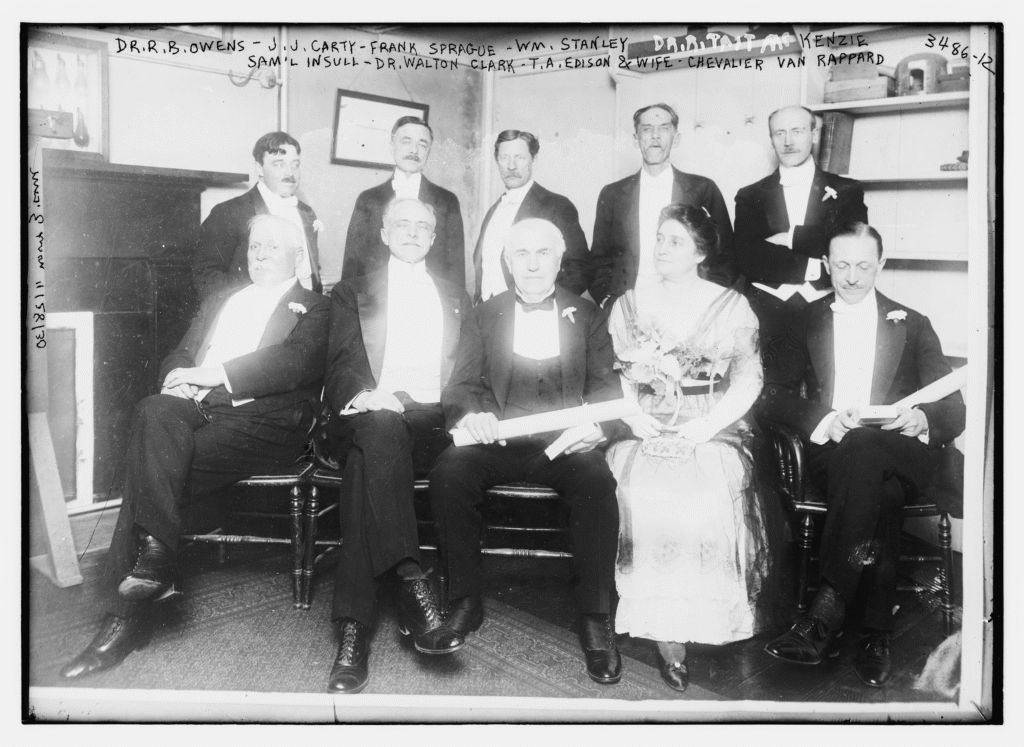

Electric power was first harnessed for commercial use in the 1880s, largely thanks to the work of inventors like Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla, and the industrial visionaries who followed them. By the early 20th century, electricity was reshaping American life, transforming how cities functioned, how factories operated, and how people lived. Yet its spread was anything but uniform.

In urban areas, where population density offered economies of scale, private utility companies rapidly installed electric lines and profited from eager customers. But rural regions—marked by low population density and long distances between homes—presented a financial challenge. Extending power lines to individual farms was costly, and the anticipated return on investment was low. For private companies focused on profits, rural America simply wasn’t worth the trouble.

Thus, electricity became a symbol of modernity and inequality at once. In the cities, electric appliances represented leisure and convenience. In the countryside, their absence became a daily reminder of exclusion.

Holding Companies and the Corporate Power Structure

By the 1920s, America’s electric industry had consolidated into a series of massive holding companies. These were financial structures in which a parent corporation owned shares in multiple subsidiaries, many of which owned other subsidiaries in turn. The result was a tangled web of corporate control that insulated top executives from accountability and concentrated market power in a few hands.

Eight such holding companies controlled more than 75 percent of the nation’s electricity generation and distribution by the end of the decade. Samuel Insull, perhaps the most famous of these corporate architects, built an empire stretching across multiple states. Though he preached efficiency and economies of scale, his vast network became increasingly difficult to manage and ethically fraught. Public utility commissions often lacked the jurisdiction—or political will—to regulate these sprawling entities.

The result was a utility industry that operated with little oversight, prioritized urban development, and systematically ignored rural needs.

The Great Depression and Collapse of the Utility Giants

The 1929 stock market crash and ensuing economic depression brought the cracks in the system to the surface. As demand for electricity fell and financial mismanagement came to light, many of the great utility empires began to unravel. Insull’s company collapsed spectacularly in 1932, triggering investigations into the abusive practices of holding companies.

Congress responded with a series of reform efforts, culminating in the Public Utility Holding Company Act (PUHCA) of 1935. The act required holding companies to simplify their corporate structures and submit to stricter federal oversight. It also laid the groundwork for a reimagining of public utility access—not as a commodity for the few, but as a shared resource to be distributed equitably.

That same year, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 7037, creating the Rural Electrification Administration (REA).

The Rural Electrification Administration: Power to the People

The REA was a bold departure from prior policy. Rather than waiting for private utilities to serve rural communities, the government would provide low-interest loans to help farmers form electric cooperatives—nonprofit, member-owned organizations that would build and operate their own distribution systems.

It was a revolutionary idea. Farmers who had never worked with electricity now learned how to erect poles, string lines, and manage substations. They became engineers, accountants, board members, and system planners. These cooperatives did not rely on distant corporations or federal agencies to run their daily operations—they were controlled locally, guided by the needs and values of the communities they served.

By the end of 1939, over 400 rural electric cooperatives had been established, bringing power to more than 1.5 million people. But the movement had only just begun. Over the next three decades, rural electrification would continue to expand, eventually reaching more than 97 percent of farms by the late 1960s.

Electricity’s Transformation of Rural Life

The arrival of electricity changed everything.

In the home, women—who had long shouldered the brunt of domestic labor—gained new tools that revolutionized daily life. Washing machines replaced scrub boards. Refrigerators eliminated the need for daily food preservation rituals. Electric irons, vacuums, and lighting brought both convenience and dignity. Studies in the 1940s estimated that electrification reduced weekly housework by 30 to 40 hours.

On the farm, electric pumps made irrigation more reliable. Barns were heated and illuminated. Milking machines improved hygiene and efficiency. Farm productivity soared.

But perhaps the most profound change was cultural. Electricity connected rural Americans to the broader world. Radios brought news, music, and political debate. Schools became better lit and better equipped. The electric line became a thread that tied isolated communities into the fabric of the nation.

Resistance and the Role of Private Utilities

Not everyone welcomed the REA. Investor-owned utilities, many still reeling from the collapse of the holding companies, viewed rural electrification as a threat. Some lobbied against the program, while others engaged in public relations campaigns to cast government power as inefficient or even un-American.

In some cases, these companies rushed to provide service to rural areas—not out of newfound altruism, but to preempt cooperative development. They often installed subpar infrastructure, delivered spotty service, or charged higher rates than REA-backed co-ops.

Despite this opposition, the cooperatives endured. Backed by federal support and driven by local commitment, they built networks that outperformed many private systems.

The Legacy of Rural Electrification

Today, the rural electric cooperatives formed in the 1930s and 1940s continue to operate. They serve over 40 million Americans in 47 states, covering 56 percent of the nation’s landmass. Many are now at the forefront of new energy debates—investing in renewables, broadband expansion, and grid modernization.

The story of rural electrification is a story of infrastructure, but also of identity. It reminds us that markets do not always serve everyone equally, and that public policy can play a powerful role in ensuring that no community is left behind.

As the United States once again faces questions about access—this time to broadband, clean energy, and climate resilience—the lessons of the REA era are more relevant than ever. It took vision, coordination, and shared sacrifice to bring light to rural America. The challenges we face today may be different, but the principles that solved them still matter.

✅ Want more?

This story is covered in-depth in our podcast episode, Darkness to Light: The Fight for Rural Electrification.

References:

- Based on content from Electrifying America: Social Meanings of a New Technology, 1880–1940 by David E. Nye (MIT Press, 1990).

- Images:

- Featured: Photo courtesy of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, from the National Archives and Records Administration (public domain).

- By Bain News Service, publisher – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs divisionunder the digital ID ggbain.19159.

- By Leon Perskie – Flickr (FDR Presidential Library & Museum) – Info – Pic, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=171293476

- Youth Electrification Program at New Deal School, Tennessee, 1930s” by Tennessee Valley Authority