Introduction

In alternating current (AC) power systems, arcs behave differently than in direct current (DC) systems. The reason lies in the natural way AC current rises and falls, crossing through zero twice in every cycle. This “current zero” moment is one of the most important concepts in power engineering, because it provides an opportunity to extinguish an arc. Understanding how arcs form and disappear in AC systems is essential for learning how circuit breakers and protective devices work.

The Nature of the AC Arc

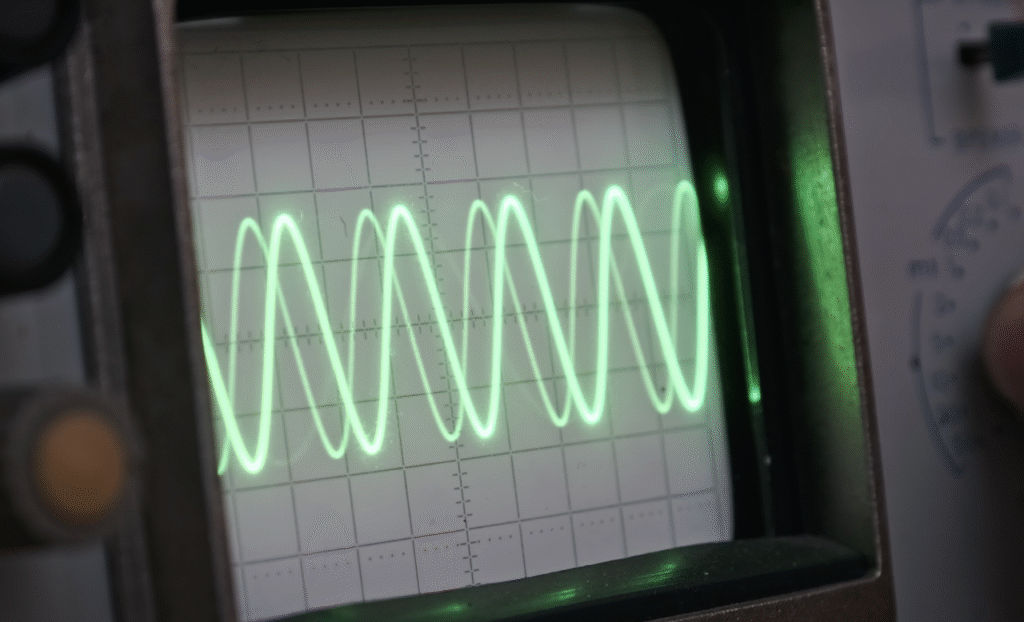

An AC arc forms when current passes between two separating contacts, ionizing the air or medium in the gap. Unlike a steady DC arc that can persist indefinitely unless forced to stop, an AC arc has a natural rhythm. As the current increases, the arc’s temperature and conductivity rise, making it easier for current to flow. As the current decreases, ionization levels drop, resistance increases, and the arc weakens.

This back-and-forth behavior means the arc does not remain constant. Instead, it pulses with the alternating current, shrinking and collapsing near current zero, then reigniting in the opposite direction as the current reverses.

The Current Zero Moment

The most critical point in an AC cycle is when the current passes through zero. At this instant, the energy sustaining the arc is at its lowest. If the arc channel loses enough heat and ionization during this pause, it cannot reignite, and the circuit becomes successfully interrupted.

However, if the surrounding medium is still ionized or hot enough, the arc may reestablish itself as soon as the voltage rises again. This makes the conditions immediately before and after current zero extremely important for reliable interruption.

Extinction Voltage and Reignition

When an arc goes out at current zero, a sharp voltage appears across the gap, known as the extinction voltage. If the dielectric strength of the gap recovers quickly, the arc stays extinguished. If not, the supply voltage can exceed the gap’s recovery capability and cause the arc to reignite.

Engineers study this relationship as a race between two processes: the recovery of the gap’s insulating strength and the rise of the system voltage. A successful interruption occurs only when dielectric recovery is faster than the voltage buildup.

Why Current Zero Matters in Circuit Breakers

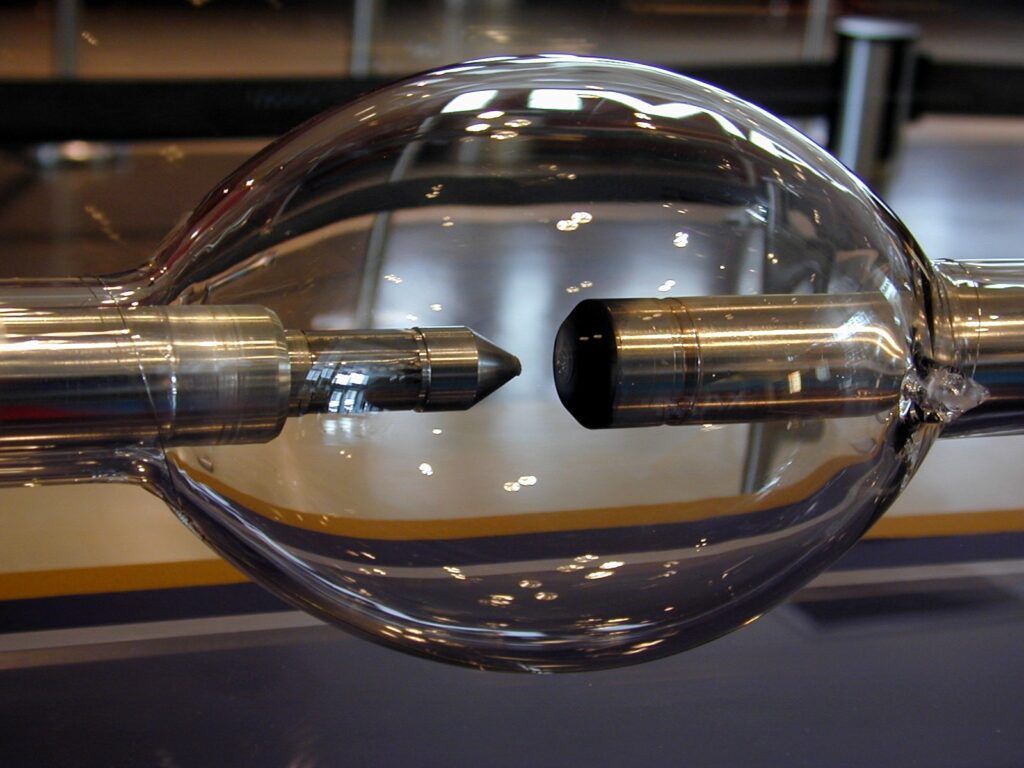

Circuit breakers depend heavily on the current zero phenomenon. In AC systems, breakers are designed to cool and de-ionize the arc channel quickly so that, when current naturally falls to zero, the arc cannot restart. Different breaker designs (air blast, SF₆, or vacuum) all rely on maximizing dielectric recovery during this brief window of opportunity.

The current zero moment also explains why interrupting AC is generally easier than interrupting DC. In DC systems, there is no natural zero crossing, so special techniques must be used to force the arc to stop. In AC systems, nature provides the opening twice every cycle, but equipment must be designed to take advantage of it.

Key Takeaways

The alternating current arc is unique because of the natural current zero phenomenon. Each zero crossing creates a chance for the arc to be extinguished, but success depends on whether the gap can regain its insulating strength before the system voltage rises again. This balance between arc de-ionization and voltage recovery forms the foundation of AC circuit breaker operation. Understanding this process is vital for anyone entering the electrical power field, as it explains both the challenges and advantages of interrupting current in AC systems.