Electricity feels like something modern; we flip a switch and lights come on, we plug in our phones, and everything just works. But the story of how humans first discovered electricity and magnetism goes way back; thousands of years before wires, power plants, or even lightbulbs.

People noticed strange forces in nature that they didn’t fully understand. These simple observations—stones that pulled on metal, or sparks from rubbed objects—were the first steps toward the science we study today.

Discovery of Magnetism: Lodestone

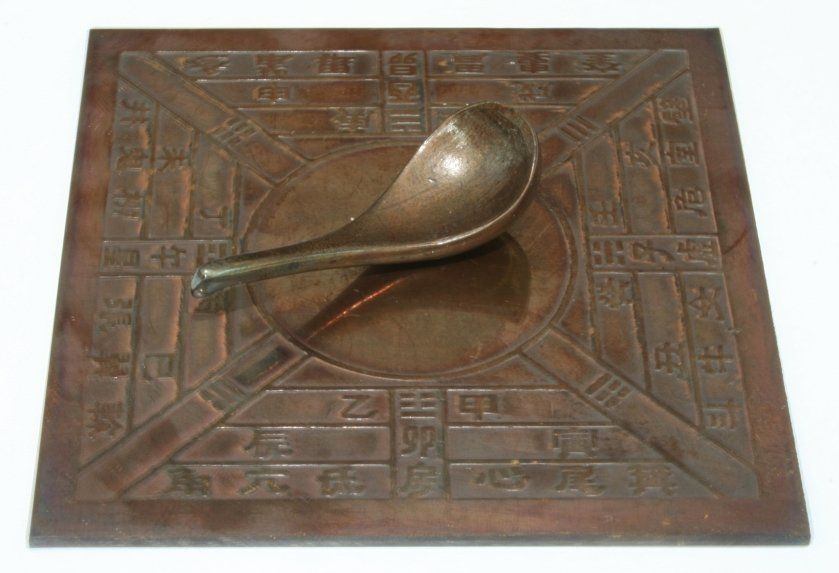

Long before anyone knew about “magnets,” people found a strange rock called lodestone. Unlike other stones, it could pull on iron. Imagine picking up a nail with nothing but a rock, it must have seemed like magic.

The Chinese noticed this effect as early as 2637 B.C. and eventually learned to use lodestones to help with navigation. They created the first compasses (206 B.C.), which always pointed in the same direction. This simple discovery changed history, letting sailors explore farther across oceans.

The Amber Experiment

Around 600 B.C., a Greek thinker named Thales of Miletus made another unusual discovery. He found that when amber (a hard tree resin that looks like golden glass) was rubbed with cloth, it could attract light things like straw or hair.

This is the first record of static electricity, the same effect you feel when you rub your socks on carpet and then get shocked touching a doorknob. In fact, the Greek word for amber, elektron, gave us the modern word electricity.

Losing Knowledge, Finding It Again

For centuries, these discoveries stayed as odd facts without clear explanations. During the Middle Ages, most of Europe forgot about them. But in China and the Arab world, people kept experimenting and writing about magnets and electricity.

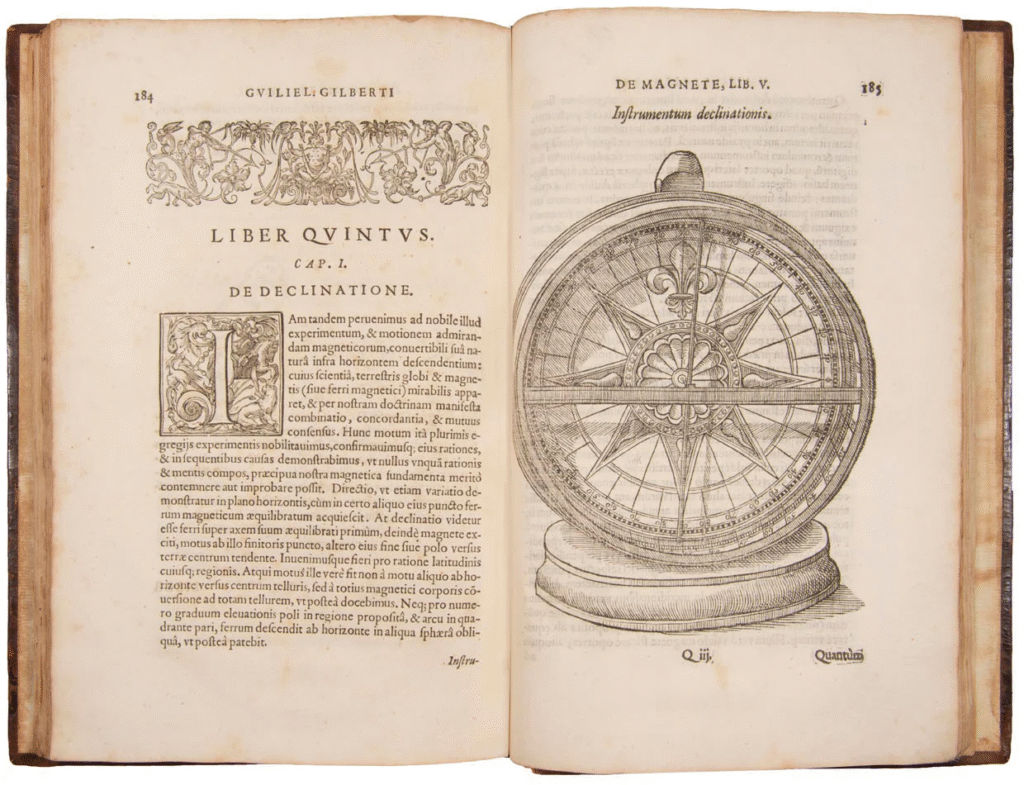

In the 1200s, a French scholar named Petrus Peregrinus studied magnets closely and described how to build a floating compass. Later, in 1600, the English scientist William Gilbert pulled everything together in a famous book called De Magnete. He even suggested that Earth itself is one giant magnet.

The First Sparks of Modern Science

By the time Benjamin Franklin flew his kite in a thunderstorm in 1752, the study of electricity had become serious science. But it all started with simple observations:

- A rock that pulled on iron.

- A piece of amber that picked up straw.

- A compass needle that always pointed north.

These small steps eventually led to batteries, light bulbs, motors, and the massive electrical systems we depend on today.

Why This Matters for You

Those new to the electrical world, it’s easy to jump straight into transformers, relays, and testing equipment. But remember, our entire field grew from small experiments done by curious people. They didn’t have labs, calculators, or even electricity as we know it. What they did have was curiosity and patience.

The lesson? Big discoveries often start with simple questions. When you notice something odd in your own studies or work, pay attention, you never know where it might lead.

References – From Lodestones to Lightning

- Meyer, H. W. (1972). A History of Electricity and Magnetism

- Chinese records on lodestones and early compasses, c. 2637 B.C. (as discussed in Meyer).

- Gilbert, W. De Magnete (1600), pioneering study on Earth’s magnetism.

- Images:

- Feature: By Ryan Somma – [1], CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5228830

- Compass: CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=553022